03.28.2023 The failure of Silicon Valley Bank a few weeks ago is eerily similar to the collapse of Bear Stearns’ subprime-backed hedge funds in September 2007, which presaged the firm’s takeover as well as the great financial crisis in 2008 – and resulted in a systemic decline in global equities. What were the warning signs then, and are there any today?

Anatomy of a market downdraft, Q1/23 edition

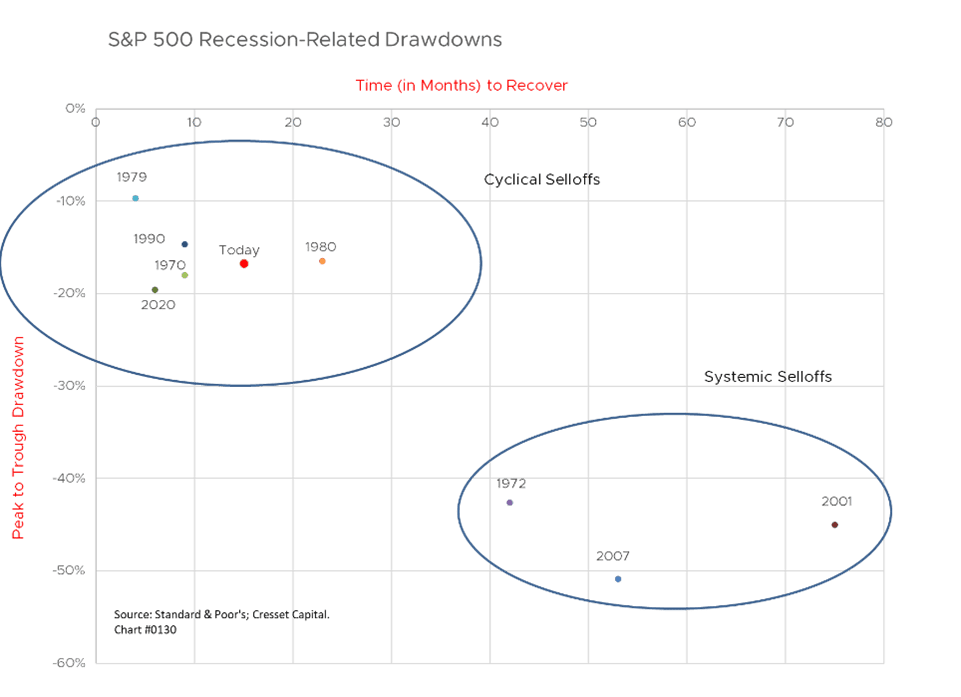

Market selloffs come in three flavors:

Technical selloffs, also referred to as corrections, is a swift, high-single-digit equity downturn and an equally quick recovery. Technical selloffs drawdown between 10 and 20 per cent and recover within 10 months.

Cyclical downturns, which are equity selloffs related to recessions, can lose up to 20 per cent and can take as long as two years to recover. Cyclical selloffs are the most common type of selloff since they’re related to the business cycle.

Systemic selloffs are the mothers of all selloffs. Thankfully, they’re rare. Systemic selloffs are characterized by market plunges exceeding 40 per cent, as investors worry about the underpinnings of the financial system. Recent history has witnessed three systemic selloffs, triggered by the wage-price spiral of 1972, the tech bust in 2001 and the financial crisis in 2007. Each of these erased between 40 per cent to just over 50 per cent in the market’s value. Systemic selloffs take between four and seven years to recover their pre-crisis peak.

We believe our current equity malaise is cyclical, not systemic. Our current drawdown sits in the middle of the range of cyclical downturns that have occurred since 1970.

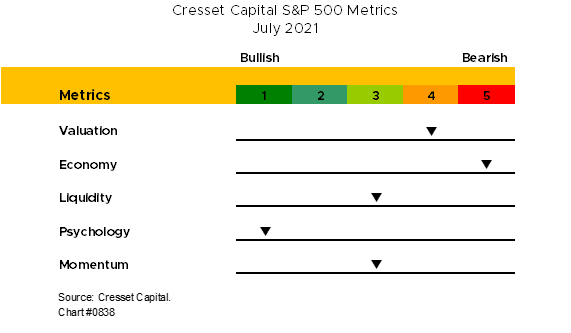

We rely on five market metrics – Cresset’s Five Factors – to gauge our current risk positioning:

Valuation: whether the market is expensive or cheap

Economic backdrop: whether the economy is expanding or contracting

Liquidity: the availability of money to borrow, spend and invest

Psychology: whether or not investors are bullish or bearish

Momentum: the prevailing direction of the equity market

Let’s break down today’s metrics and compare them to 2007, a perilous period for equity investors.

Valuation

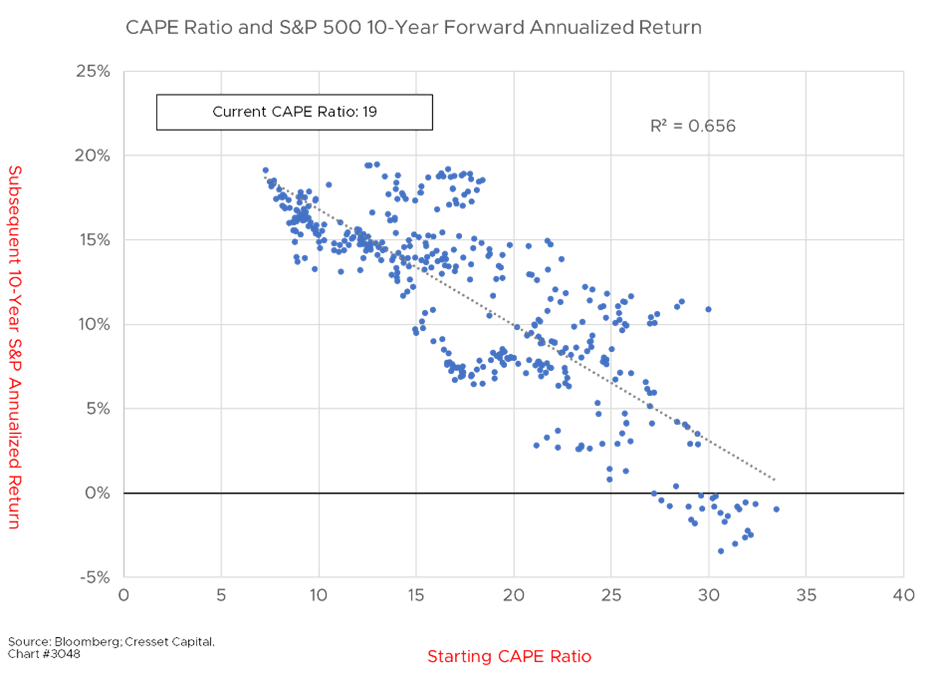

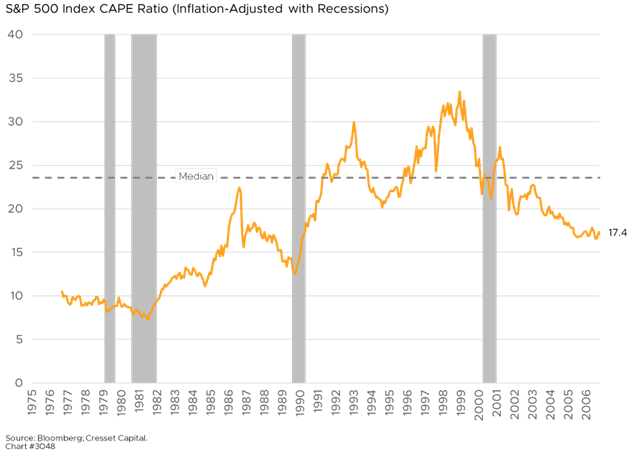

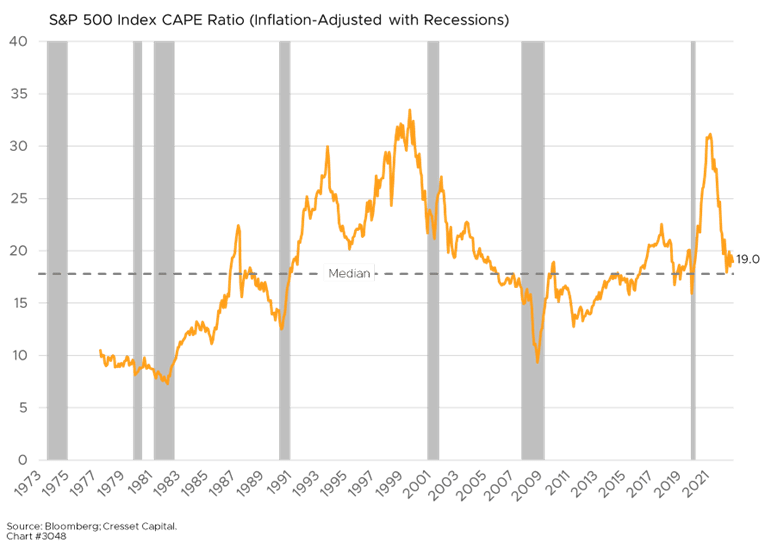

The cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio, pioneered by Yale professor Robert Shiller, looks at today’s market price relative to the average real earnings per share over the previous 10-year period to smooth out cyclical fluctuations in corporate profits. It’s been a good, long-term measure of value. The CAPE ratio has been a strong influence over the market’s subsequent 10-year return, explaining about 65 per cent of the variation in 10-year annualized performance.

In September 2007, when Bear Stearns first made news, the S&P 500’s CAPE ratio was over 17x, reasonably priced by historical standards. Our scatter study implied a subsequent 10-year annualized return of about 10 per cent. The actual annualized 10-year return through 2017 was 7.4%, but not before plunging more than 25 per cent over the next 12 months and 50 per cent through February 2009.

Today’s CAPE ratio is about 19x, which is slightly higher than historical norms. Our model projects an annualized return of eight to nine per cent over the next 10 years. With a 10-year Treasury yield in the threes, an eight or nine per cent annualized return would be welcome.

Economic backdrop

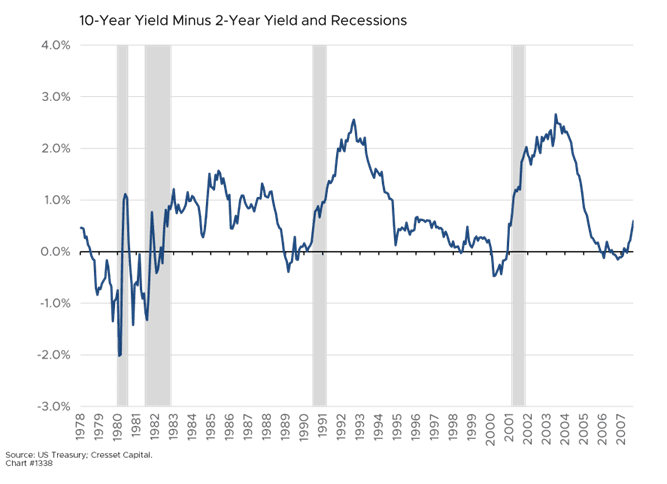

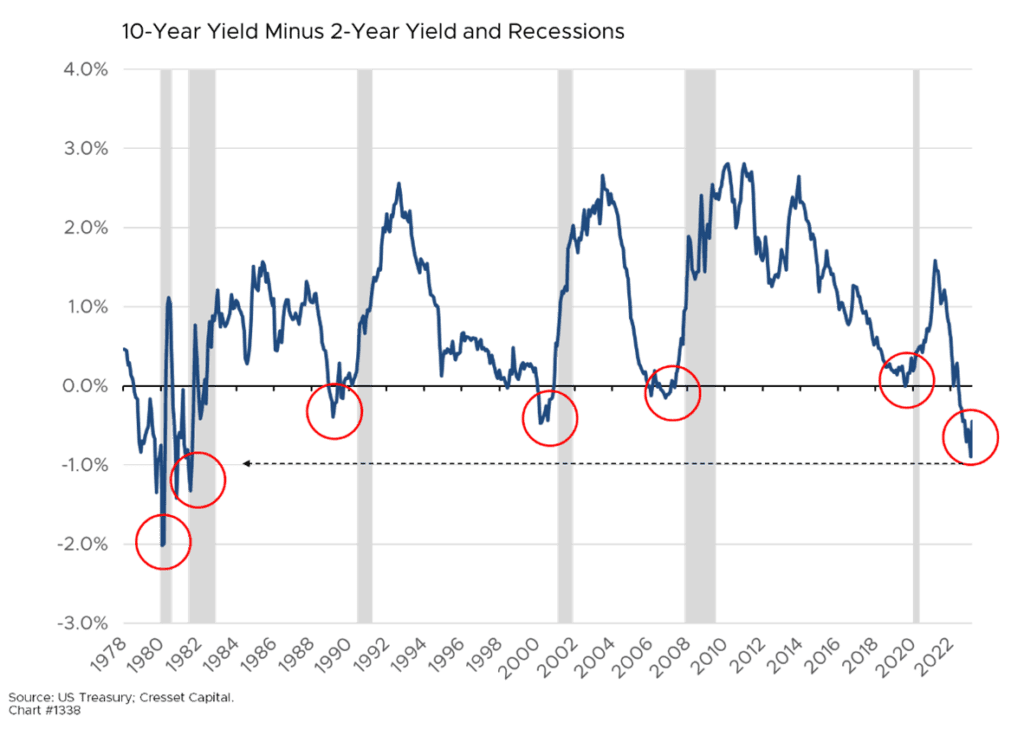

Like today, the yield curve between 2-year and 10-year Treasury notes inverted going into 2007, although it steepened incrementally in the second half of that year. That inversion, albeit brief, was enough to signal recession, into which we plunged a 18 months later.

Today’s yield curve is also signaling recession, with the yield differential between 2-year notes and 10-year notes at its steepest since the early 1980s. Today’s economy does not present a favorable backdrop for corporate profits, unfortunately.

Liquidity

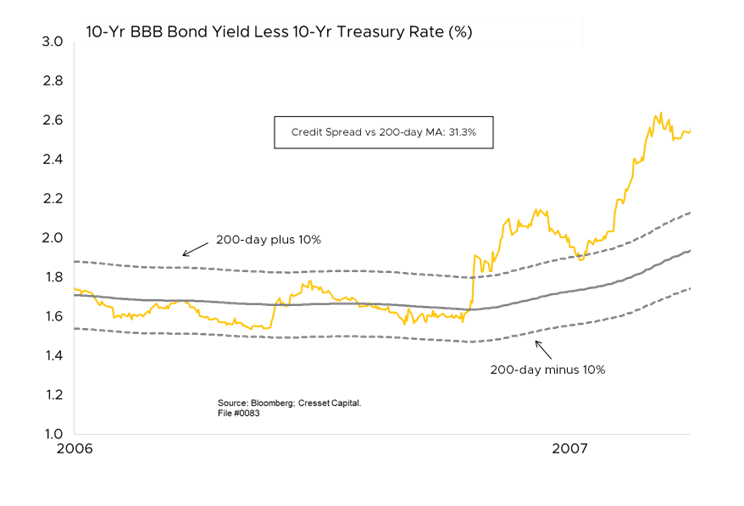

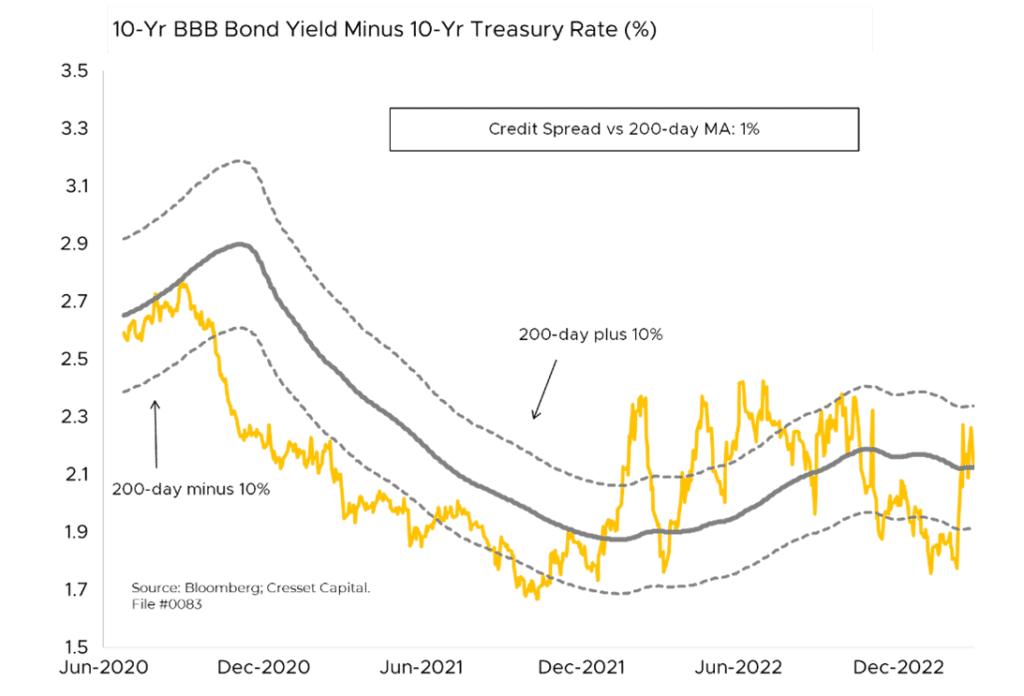

One of the biggest differences between today’s environment and the one on the precipice of the financial crisis in 2007 is the liquidity profile. Credit conditions broke down in July 2007, as the yield premium lenders required to extend credit to BBB-rated borrowers widened, reflecting caution and a move to “risk-off.” History has shown that market performance in a negative credit environment is, on average, half of that in a favorable credit environment.

Notwithstanding the recent banking sector turmoil, today’s liquidity environment is favorable, having moved to risk-on in December 2022. Though market turbulence over the last couple of weeks has spurred spread widening, most of this was prompted by a sudden plunge in Treasury yields, not by a deterioration in credit conditions.

Psychology

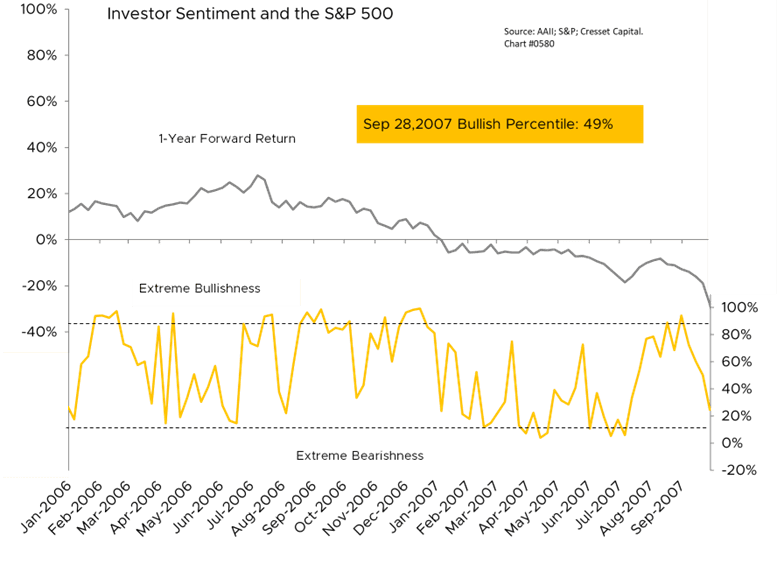

Psychology is a contrary indicator, and only useful at extremes. Widespread bullishness reflects investor complacency, which is subject to disappointment as expectations and reality collide. Widespread bearishness, on the other hand, is an indication of low expectations among investors, increasing the likelihood of an upside surprise. While investor attitudes were neutral going into Q4/07, as early as August 2006 investors had been collectively optimistic, with bullish readings hitting the top decile of their historical range. News of Bear Stearns’s hedge fund problems certainly deflated some of their enthusiasm, although bearishness wasn’t pervasive until later in 2008.

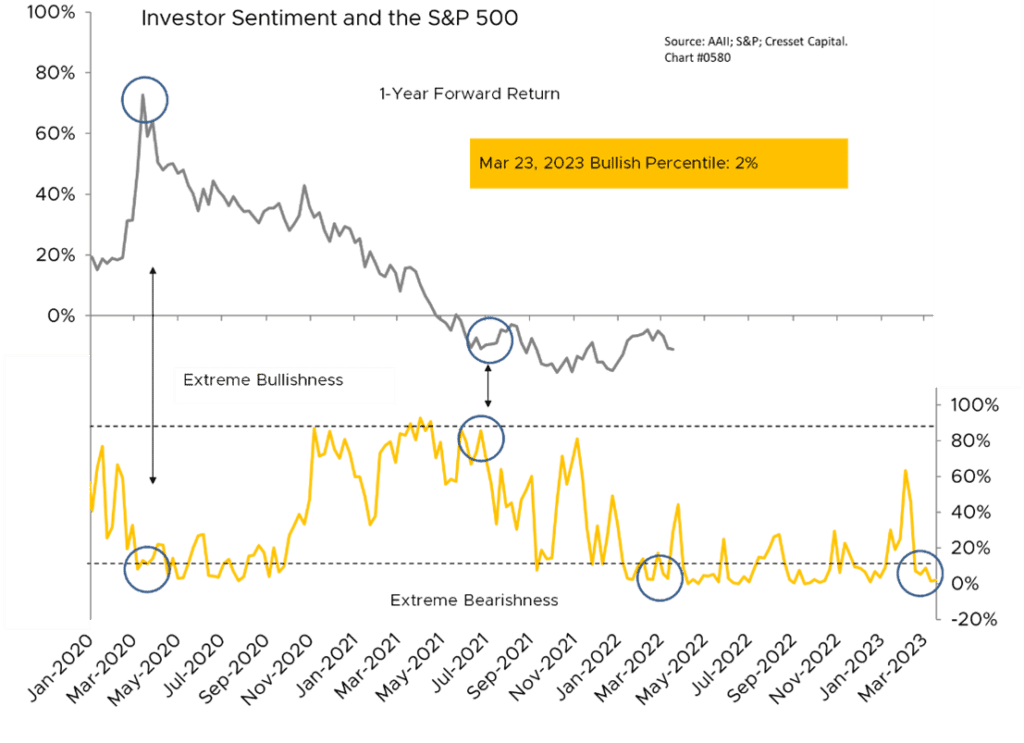

Today, investors are universally pessimistic, with bullishness situated in the 2nd percentile of its historical range. That’s good news! Pervasive handwringing suggests that anyone who’s inclined to sell has already sold. With expectations running this low, reality is likely to surprise on the upside.

Momentum

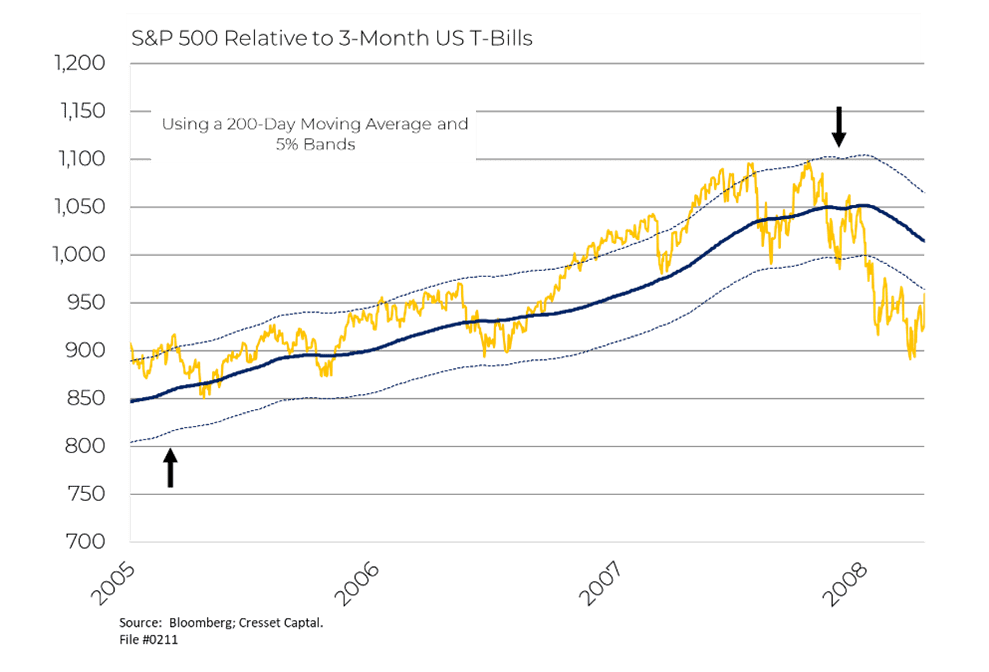

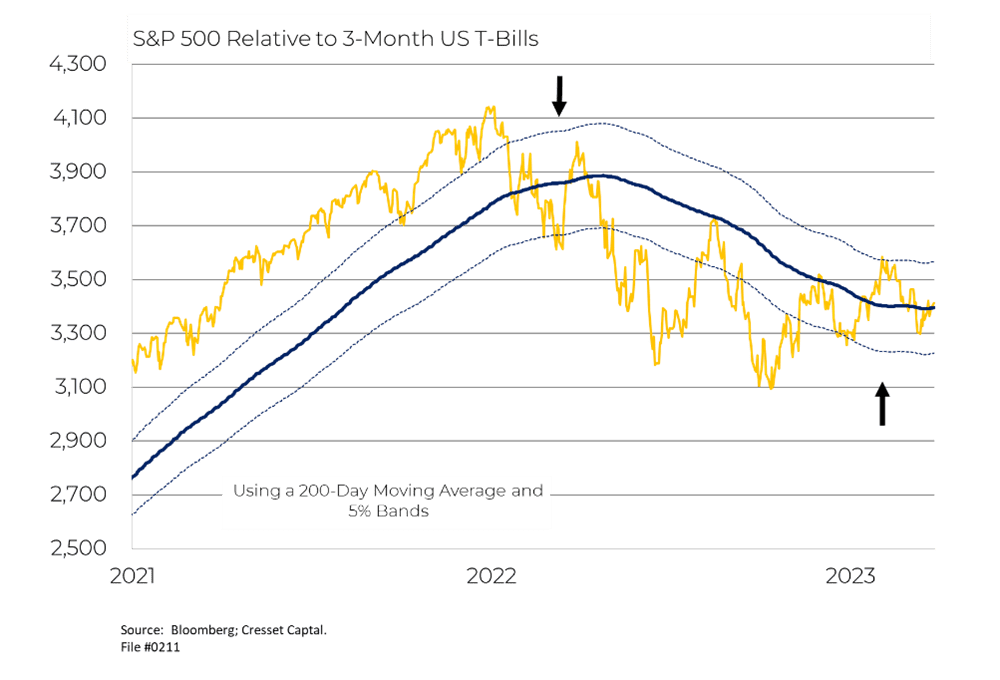

A market in motion tends to stay in motion unless otherwise acted upon. The S&P 500’s momentum broke down in November 2007, suggesting a bearish trend. Hindsight tells us it was a valuable sell signal. Between November 2007 and March 2009, US large-cap market caps were cut in half, with a momentum buy signal not reappearing until Q2/09.

Today’s market is enjoying positive momentum, having broken to the upside in December 2022. The recent selloff has not been powerful enough for the index to break more than five percent below its 200-day moving average.

Our five factors combined suggest we’re not entering a systemic downturn. We acknowledge that equities are fully valued here at home, and that better equity opportunities are available overseas. The US economic backdrop is troubling, with the Treasury yield curve flashing recession. But liquidity is adequate – even though banks are tightening, bondholders remain willing to make loans. Investor bearishness is a positive, because everyone is already positioned for problems. Lastly, momentum, while not powerful, is favorable, suggesting further gains ahead.

Bottom line: While we’re still underweighting equity risk, with underexposure to US large caps, we’re sanguine that we’re not entering the next systemic selloff. Like the Fed, however, we remain data dependent. To paraphrase John Maynard Keynes: when the data change, we’ll change our opinion.