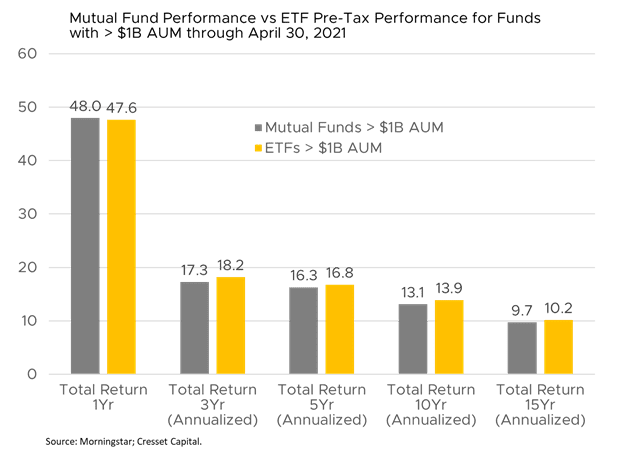

5/18/21: Active management, which has been under pressure for decades, is now facing a potential new headwind: higher tax rates. Actively managed mutual funds have struggled to keep pace with the market averages over most time periods when fees are taken into consideration. Comparing the performance history of the largest mutual funds against exchange traded funds (ETFs) offers some clues. Mutual funds with over $1 billion in assets tend to be both actively and passively managed, while the largest ETFs are virtually all passive. The last 12 months was a favorable environment for stock picking, as the pandemic drove a wedge between winners and losers. Prior to the pandemic, for example, Netflix and Disney were industry rivals. The stay-at-home order in response to the COVID-19 outbreak was the worst-case scenario for the nation’s preeminent theme park operator, but it was a boon for video streaming. Disney pivoted by launching “Disney+” later that year and eventually rallied. Yet, despite the favorable environment for active management, mutual funds only fractionally outpaced ETFs over the last 12 months. Longer term, the results were worse, as exchange traded funds on average consistently outperformed their mutual fund counterparts over three, 10 and 15 years.

Adding tax considerations to the analysis highlights another impediment facing active management, particularly among US large-cap managers. Actively managed mutual funds have two strikes against them relative to passively managed ETFs. First, actively managed strategies require portfolio turnover as portfolio managers buy attractively viewed stocks and sell relatively unattractively viewed stocks. Turnover often generates capital gains, given that markets tend to rise over time. Moreover, realized capital gains create phantom taxes to fund holders in the year they’re realized, even though the holder may have no intention of selling. Additional gains may be generated to raise liquidity to meet shareholder redemptions, which occur throughout the year. Those gains are also passed along to existing shareholders regardless of their investment time horizon. As a result, long-term holders are forced to shell out capital gains taxes even though they didn’t sell their holdings. Over time, these tax liabilities multiply to eat into longer-term performance. Over the last 10 years, taxes have cost investors in the largest actively managed mutual funds between two and three percentage points per year. We estimate that a 40 per cent capital gains rate would knock another percentage point off these funds’ after-tax annualized returns.

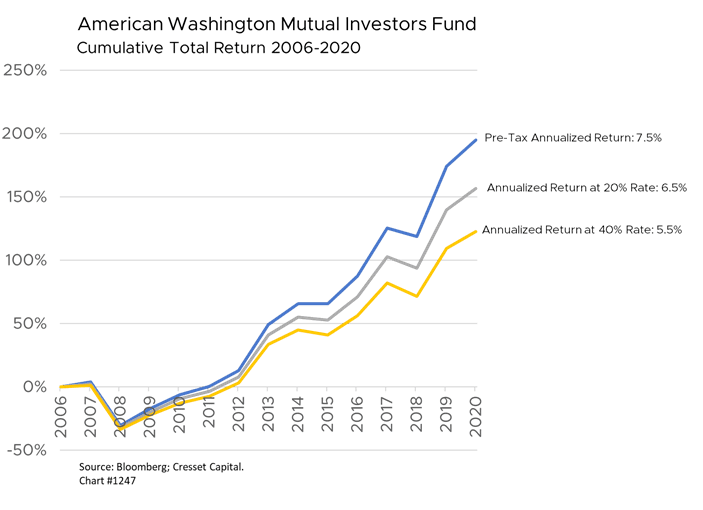

Passive strategies and lower fees have been a longer-term recipe for success, particularly among US large caps. They’re also more tax efficient than mutual funds. Of course, long-term ETF holders, like holders of mutual funds, owe taxes on any dividend income generated, but ETF holders are not subject to capital gains taxes until they liquidate the fund. That means their tax liability does not depend on the actions of other shareholders. Between 2006 and 2020, the S&P Depository Receipt (SPDR) 500 fund, one of the nation’s largest ETFs at $368 billion, delivered an 8.7 per cent annualized pre-tax return to its shareholders. Imposing a 20 per cent dividend tax rate shaves roughly 0.4 per cent off the fund’s annualized return. A 40 per cent rate pulls the annualized return down another 0.5 per cent, to about 7.8 per cent. Over that same period, the American Washington Mutual Funds, a $153 billion behemoth, expanded at an annualized 7.5 per cent pre-tax rate, trailing the index by 1.2 per cent per year. Adding a 40 per cent capital gains tax rate would slice the mutual fund’s return to just 2 per cent per year.

The Biden administration is busily negotiating the expenses and revenues related to its American Families Plan. Where the bill ultimately ends up will be subject to a substantial amount of sausage making. In the meantime, it’s reasonable to expect that investors will wind up with higher tax rates. Bottom line: tax efficiency is a critical component of investment decision making. The higher the tax, the more bearing it has on the performance of your investments. Please contact your Cresset advisor to review your investment tax efficiency.