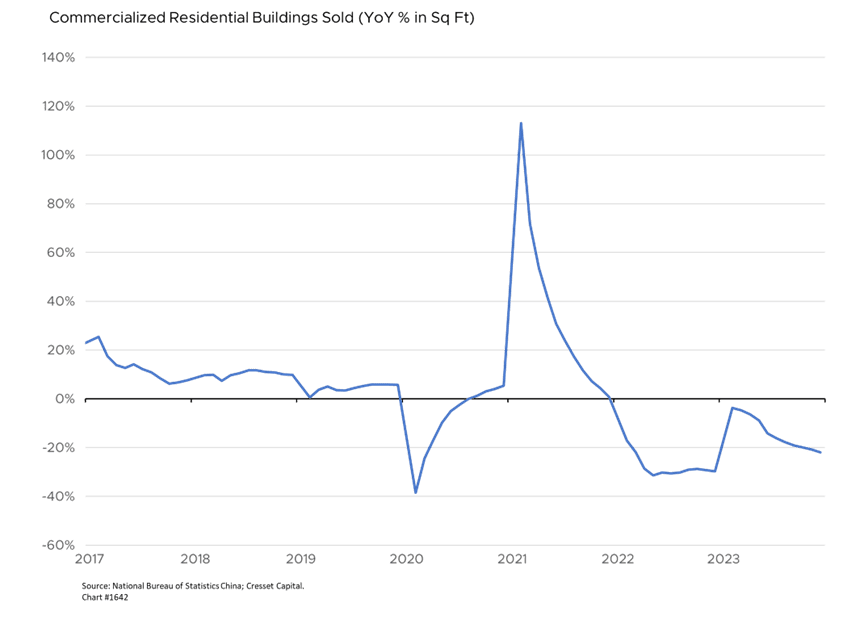

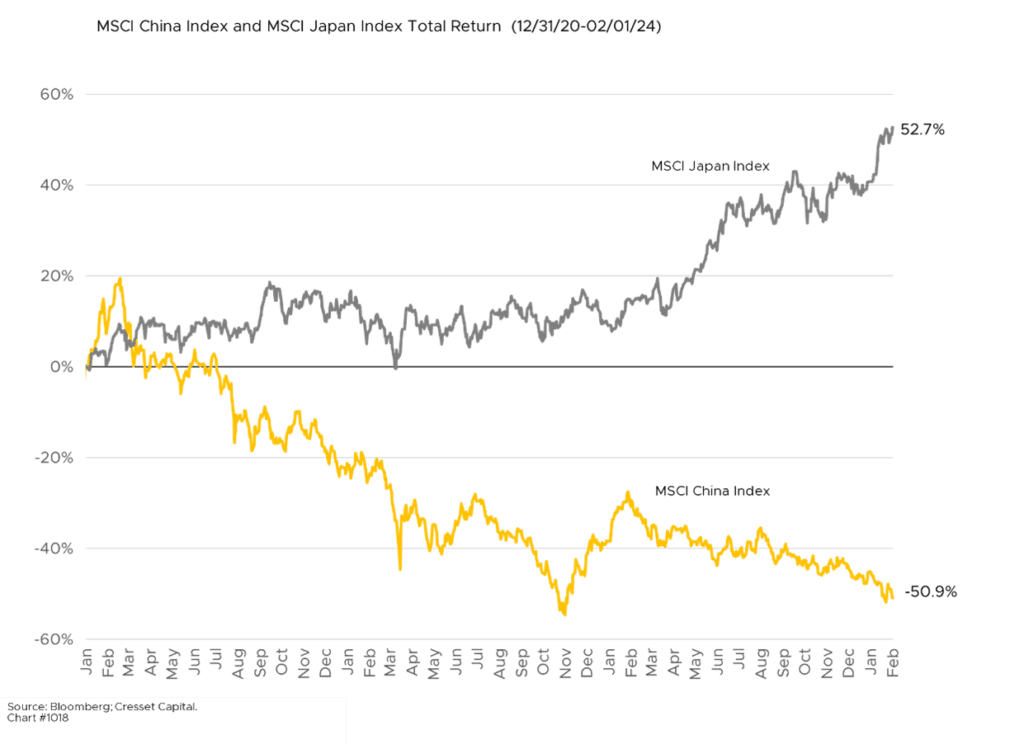

2.2.2024 Investors are hopelessly pessimistic about the outlook for China’s economy, and that view has been hard to ignore lately as Beijing’s growth-inducing policies have led to an explosion of debt. Real estate, a keystone in the country’s growth initiatives, has suffered from overbuilding and speculation, and January witnessed a court order for the forced liquidation of Evergrande, one of the companies that exemplified China’s debt-fueled building boom, after it amassed $300 billion in liabilities. Meanwhile, home prices fell the most in nearly nine years in December, as property sales plunged 17 per cent. Multi-family building construction plunged 22 per cent over the 12 months ended in December. Meanwhile, China’s stock market has plunged in value by $6 trillion over the last three years, erasing half its end-2020 value. Is investor pessimism warranted?

We see no evidence that the widespread valuation contraction in both properties and equities poses a systemic risk to the financial system of the world’s second-largest economy. China’s economy will certainly feel the pinch from a continued decline in household demand. Equities, by the way, represent just a fraction of the household wealth represented by real estate in China.

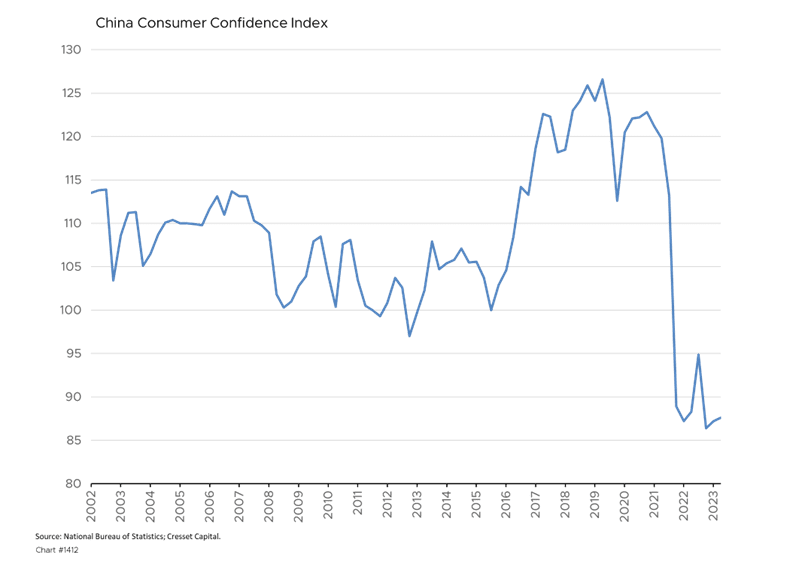

Deteriorating wealth has led to a widespread erosion of confidence among Chinese households, as pessimism about the future expands. A series of government campaigns to address the malaise and narrow the wealth gap have dealt a significant blow to businesses over the last several years. Beijing recently injected 2 trillion yuan ($280 billion) into the economy, and lowered banks’ reserve requirement to prop up the Mainland and Hong Kong stock markets. It’s becoming clear that government stimulus has not been enough to revitalize the country’s property sector. Policymakers have taken incremental steps, like lowering mortgage rates and down payments and cutting lending costs, rather than aggressively curtailing the debt-dependent growth initiatives that fueled their current problems.

The Chinese are voting with their wallets as well as their feet. Businesses and households have been moving money overseas at the highest rate in seven years, according to Chinese government statistics reported by National Public Radio. Many of the wealthy are emigrating, not to Canada or the US, but increasingly to Japan, a culturally compatible and geographically closer country. It is estimated that 13,500 US dollar millionaires emigrated to Japan, a country in which the Chinese already make up the largest group of foreign nationals. Beijing allows each citizen to purchase no more than $50,000 in foreign currency each year to prevent capital flight, so the Chinese are resorting to the shadow banking system and other techniques, like art auctions, to shift their wealth abroad.

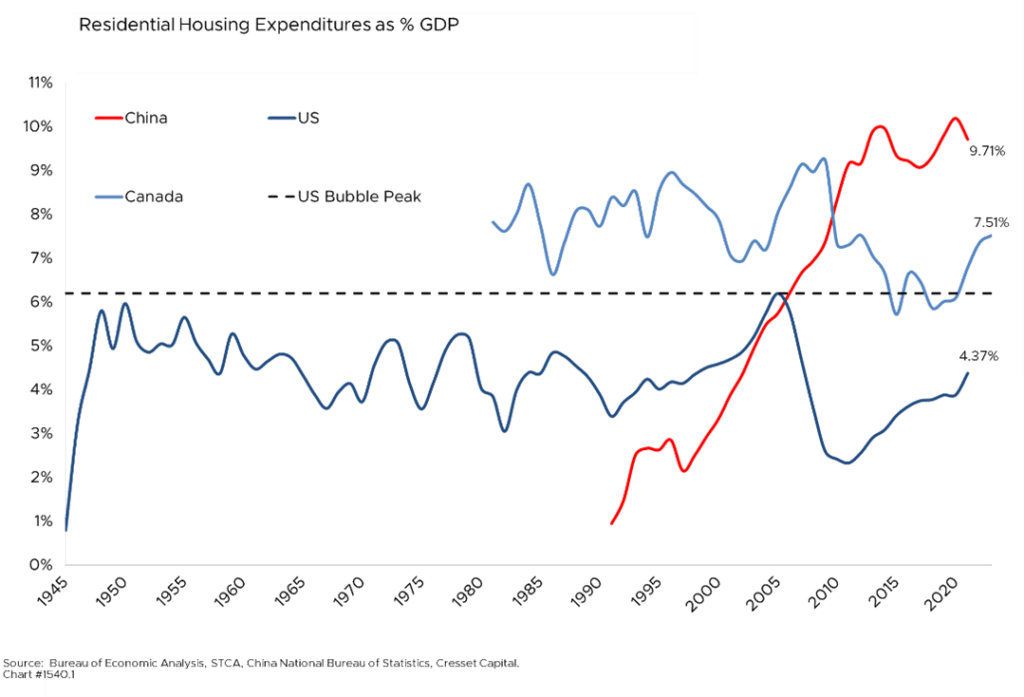

While we believe the current situation does not present a high risk of systemic financial risk to China, we do see risks from an investment perspective. The property sector accounts for a large chunk of China’s GDP and household balance sheets. Industries related to the property sector account for about one-third of GDP – more than twice the size of the property sector in the US relative to the size of the economy. At last reading, housing expenditures represented nearly 10 per cent of China’s GDP, substantially higher than the six to seven per cent level reached in the US at the peak of our housing bubble. Unlike the US experience, we’re not anticipating a financial crisis in China because the majority of lending is controlled by the state. But we do expect property deflation to weigh on China’s economy for several years to come.

Policy unpredictability is another risk facing investors in China. Periodic government crackdowns on industries, like tech, undermine investor confidence. The Communist Party’s heavy-handed governance and capricious attitude toward foreign investment creates corporate uncertainties and market instability. Foreign companies are increasingly shifting production out of China. Last year, US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo complained to Chinese officials that US companies face unique challenges, such as fines and ambiguity concerning China’s new anti-espionage law, in addition to issues including intellectual property theft and competition with subsidized Chinese firms.

Taiwan risk is a perennial threat that overhangs investors in China like the sword of Damocles. When Western investors were unable to extricate their imbedded businesses in Russia after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, they woke up to the risk that if China were to invade Taiwan, a freeze on foreign assets in China would be imminent.

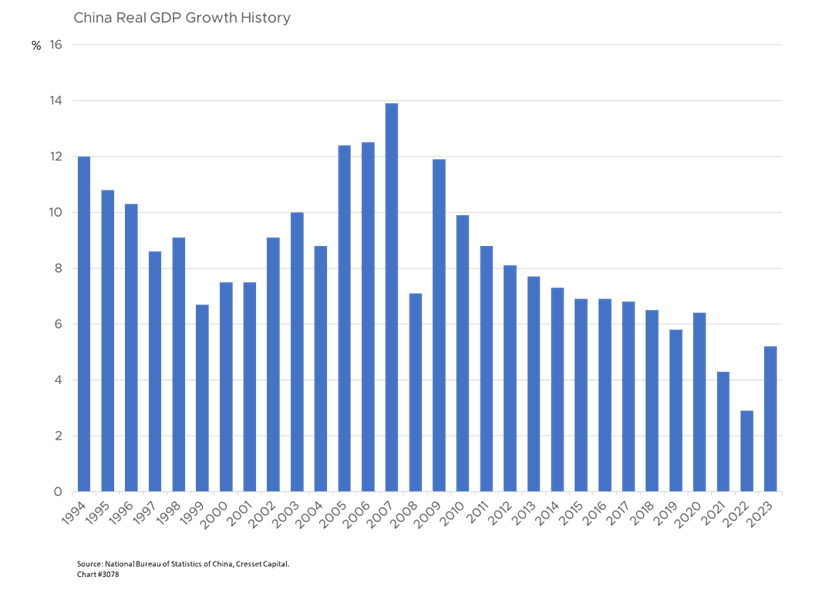

Meanwhile, the country’s economic growth trajectory is slowing. Economists forecast GDP to expand five per cent this year, below China’s six per cent growth target and the country’s historical trend. Growth is half of what it was at the height of globalization in the early 2000s. Exports, a key growth driver over the years, have fallen on weaker foreign demand as globalization runs its course. We don’t expect Chinese export volumes to again approach the level they reached during the height of globalization.

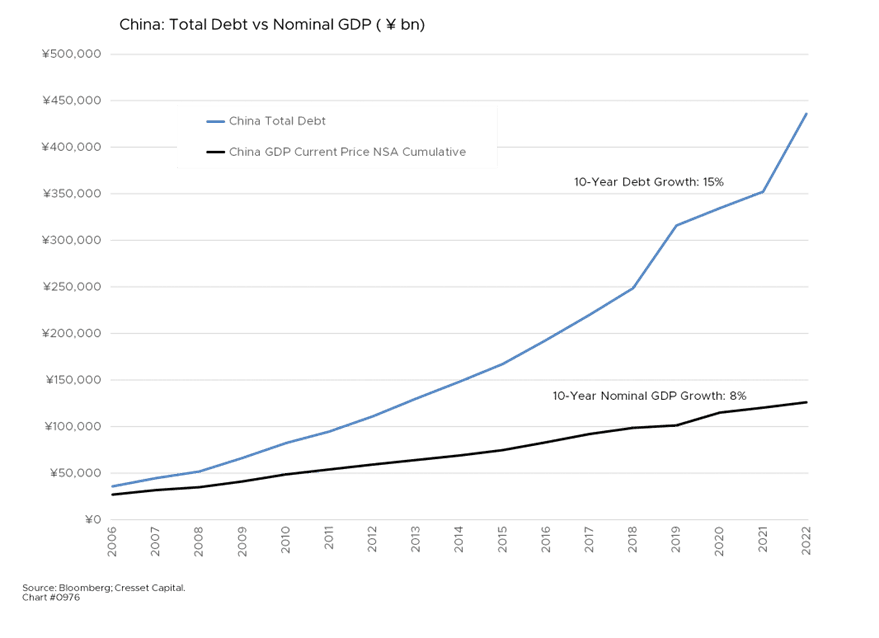

China’s debt levels, both corporate and government, are swelling at a time when property values are dropping and threatening financial stability. Local government finances are deteriorating along with the slide in land sales. China’s debt has compounded at a rate nearly double that of nominal GDP over the last 10 years. While this trend is not at all foreign to US investors, China’s debt level will limit Beijing’s fiscal flexibility.

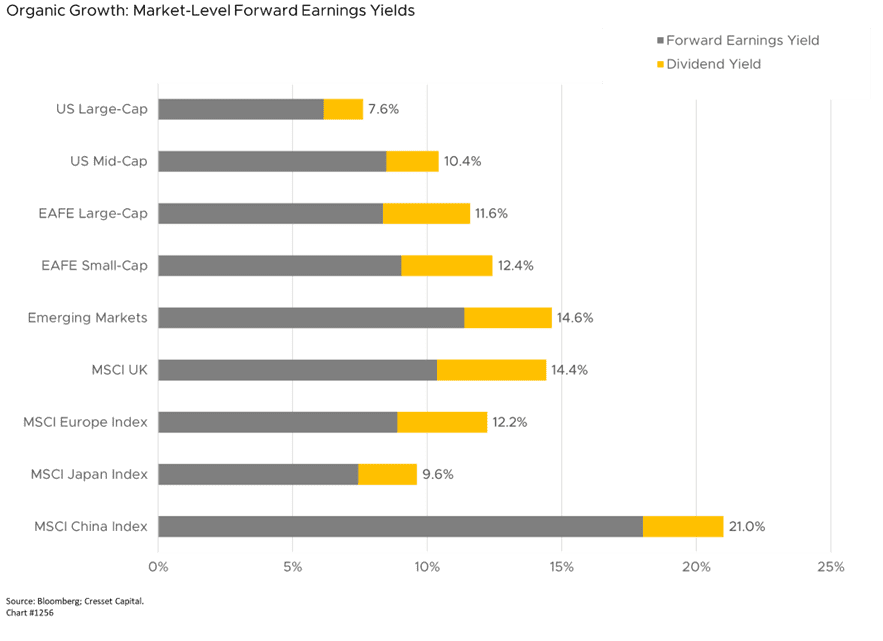

Before we turn our back on investing in China for the next few years, we should consider a few of its favorable attributes. The Chinese equity market is attractively valued after its sizable decline. It stands at an 8.8x price-to-earnings ratio and 1x book value, more than one standard deviation below its historical average, according to Global X. Analysts are anticipating 14 per cent earnings per share growth this year. China’s forward earnings yield plus dividend yield is over 20 per cent, underscoring its undervaluation relative to the rest of the world.

Longer term, China still possesses growth potential, given the size of its workforce and expanding middle class. Moreover, the country is also positioned as a global leader in alternative energy, like solar and battery technology, thanks to government-directed investments and access to rare earth minerals. Industries beyond real estate could also be poised to benefit from government stimulus – given China’s aging population, healthcare/biotech, factory automation and robotics could be among them.

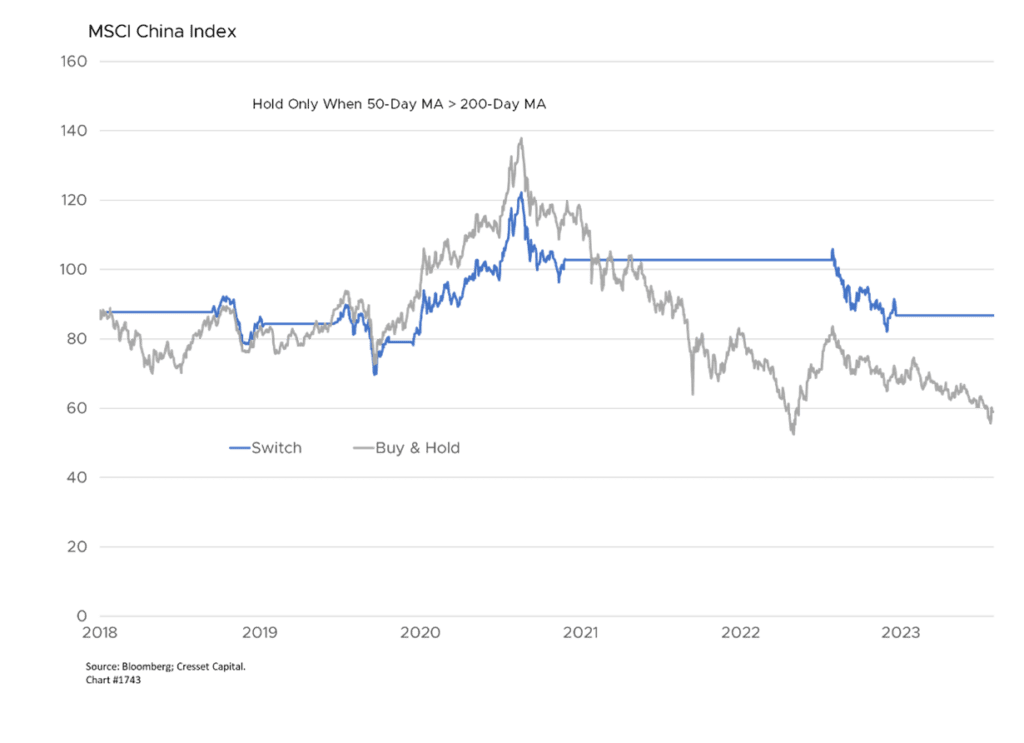

Bottom Line: China’s growth prospects remain cloudy, as the country reckons with its overcapacity in real estate. Reforms are undoubtedly needed to reinvigorate growth. Beijing must reduce its role in the economy to spur innovation and encourage consumer spending. While Communist officials are desperately trying to arrest the stock market rout, Beijing needs to embrace a laissez-faire attitude toward markets and reduce government control of business to stabilize long-term growth. Unfortunately, President Xi’s central control philosophy runs counter to the markets’ demands. While Chinese equities are cheap, we require more evidence that global investors are embracing the market. Positive momentum and favorable relative strength would be an indication that investors recognize China as a cheap market that has turned the corner. For now, though, momentum is working the other way.