Key Observations:

- So far AI hasn’t brought a jobs apocalypse

- Job tasks are changing, but entire occupation categories are not yet becoming extinct

- AI creating bifurcated labor market; impact differs by occupation and skill level

- Shrinking white collar employment could dent consumption and GDP growth

- Higher productivity could lead to higher wages, or only to corporate cost savings

Artificial intelligence (AI) has evolved from a niche technology into a transformative force reshaping nearly every sector of the global economy. Since the introduction of generative AI tools such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT in 2022, businesses have embraced automation, data-driven decision-making, and machine learning at unprecedented rates. This rapid adoption has sparked a fundamental question: Will AI destroy jobs or redefine them?

So Far AI Hasn’t Triggered a Jobs Apocalypse

While technology optimists argue that AI will augment human productivity and create new forms of employment, skeptics warn of widespread displacement and shrinking career paths for white-collar workers. The truth, as current evidence shows, lies somewhere in between. AI is not triggering mass unemployment, but it is reshaping labor markets, altering skill requirements, transforming industries, and amplifying inequalities among workers and sectors.

Despite fears of an impending “jobs apocalypse,” empirical studies suggest that AI’s labor market effects have been moderate so far. A joint study by Yale University’s Budget Lab and the Brookings Institution found little measurable disruption in US employment levels since the release of large language models. The research analyzed labor market data across industries and concluded that generative AI’s impact remains comparable to earlier technological shifts like the introduction of computers and the internet.

AI Tools Are Changing Job Tasks, But Not Yet Replacing Entire Occupations

Because AI adoption remains uneven across firms, organizations are still experimenting with how to integrate AI effectively into workflows. Recent data suggests the mix of IT roles is changing faster than in the broader economy, suggesting that instead of destroying jobs, AI is currently rearranging who does what, and how they do it.

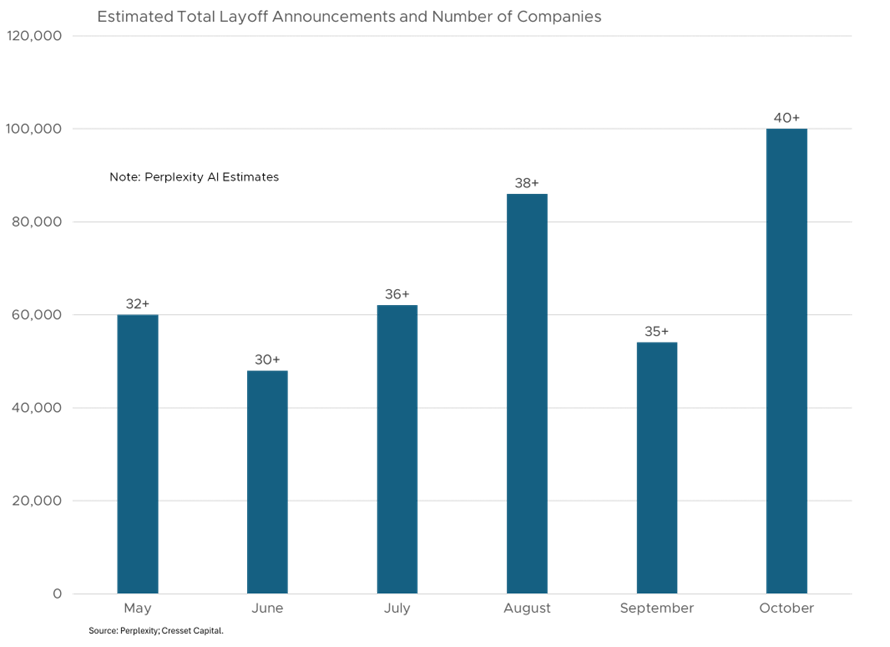

While macro data paints a sanguine picture, recent corporate layoff headlines are troubling. Over the last couple of weeks, major employers such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta announced tens of thousands of layoffs, citing AI implementation. Amazon’s decision to cut 14,000 corporate roles was described as an effort to “organize more leanly” and capitalize on AI-driven efficiency. Internal Amazon documents referenced by The New York Times revealed a long-term strategy to automate up to 75 per cent of warehouse operations and reduce new hiring by over 600,000 roles through implementing robotics and machine learning. At Microsoft, the rise of AI coding tools such as GitHub Copilot corresponded with a 9,000-person workforce reduction, while Meta and Salesforce cited AI-driven efficiencies for cutting thousands more positions.

These announcements have contributed to what Financial Times calls a “white-collar recession.” Knowledge workers, once considered insulated from automation, now face a hiring freeze across finance, consulting, technology, and management. That said, research by technology consulting firm Gartner found that fewer than one per cent of global layoffs in 2025 could be directly linked to AI productivity gains. Most companies are using AI as a strategic narrative to rationalize traditional cost-cutting.

“Labor Hoarding” Has Morphed Into “Growth Without Hiring”

Many firms have embraced a “growth without hiring” model, expanding output without expanding headcount. Analysis from The Wall Street Journal found that companies like JPMorgan Chase, Walmart, and Goldman Sachs are intentionally holding staffing levels flat while investing heavily in automation and AI. Walmart, for instance, expects to maintain a stable workforce over the next three years even as its revenues grow. The company is investing in predictive analytics and robotics to increase efficiency per worker. Similarly, Intuit’s finance division now requires managers to justify every replacement hire, asking, “Can AI handle this instead?”

This shift marks the end of the pandemic-era phenomenon known as “labor hoarding,” where companies retained workers out of fear of future shortages. According to data from Challenger, Gray & Christmas, US firms announced nearly 950,000 job cuts through September 2025 – the highest since the COVID-19 pandemic – signaling that employers are once again comfortable reducing staff when efficiency tools are available. Cresset estimates suggest that more than 40 employers announced at least 100,000 additional job cuts in October.

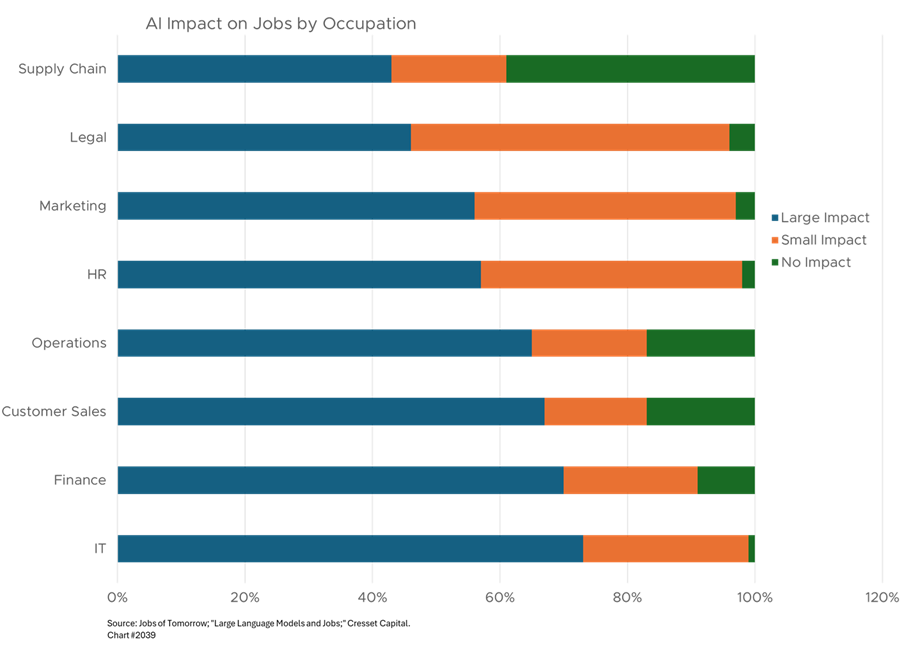

AI Creating Bifurcated Labor Market; Impact Differs by Occupation and Skill Level

- White-collar and professional services: Roles in marketing, human resources, accounting, and customer service are the most exposed to automation. AI systems can draft reports, analyze data, and handle client communications faster than junior employees, reducing demand for entry-level workers, with the largest impact on recent college graduates.

- Tech sector: Paradoxically, even technology companies are cutting jobs. Despite soaring profits from AI investment, firms like Microsoft and Meta are trimming software and managerial positions, shifting resources toward AI infrastructure and research.

- Blue-collar and technical jobs: Demand for skilled trades, logistics, and AI maintenance technicians remains strong. Amazon’s Shreveport facility, for example, employs over 160 robotics technicians – positions paying above the warehouse average.

- Healthcare, construction, and energy: These sectors continue to experience labor shortages, as automation complements rather than replaces human work. AI assists in diagnostics, project design, and data management, but physical and interpersonal tasks remain human-driven.

The result is a bifurcated labor market, with high-value technical and creative roles on one end, and low-wage service or trade jobs on the other and shrinking opportunities in the middle.

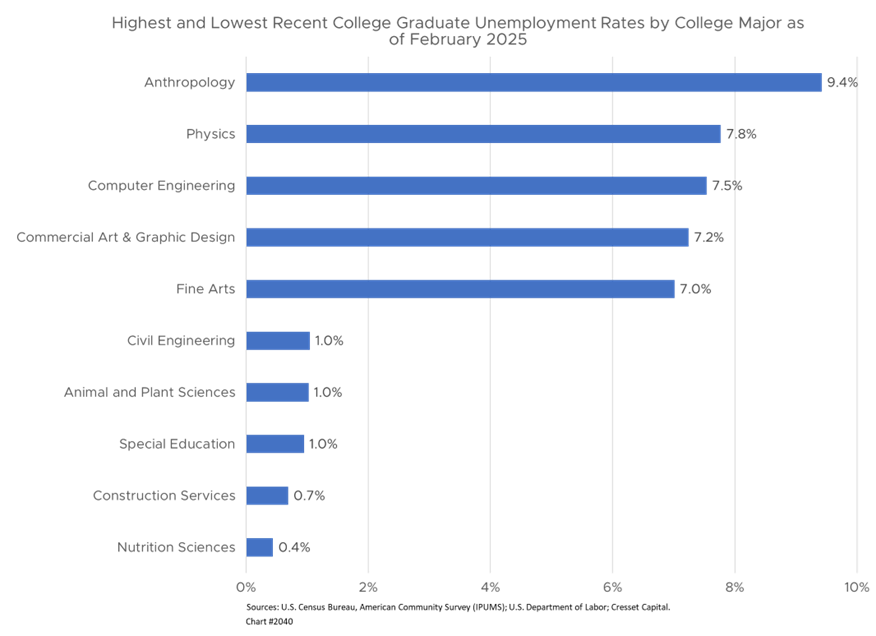

Labor market economists are debating who AI threatens more: young entrants who are generally hired as research assistants, or seasoned professionals who draw relatively larger incomes. Studies from Stanford and Harvard show a sharp, nearly 20 per cent decline in junior coding roles since late 2022, suggesting that AI tools can handle many entry-level programming tasks. This “hollowing out” effect may limit opportunities for new graduates to build experience. Recent graduates with computer engineering undergraduate degrees have among the highest unemployment rates this year.

Others argue that mid-career workers could face greater risk. As AI systems replicate specialized knowledge, the value of long-held expertise declines. Younger workers might adapt faster to integrating AI tools, while older professionals could struggle to retrain.

The likely outcome is not uniform replacement, but career compression, with fewer middle-management roles and flatter corporate hierarchies. Firms will likely employ small teams of AI-augmented juniors supervised by a handful of senior experts, potentially eliminating intermediate layers of experience.

AI Impact on White Collar Employment Could Dent Consumption and GDP Growth

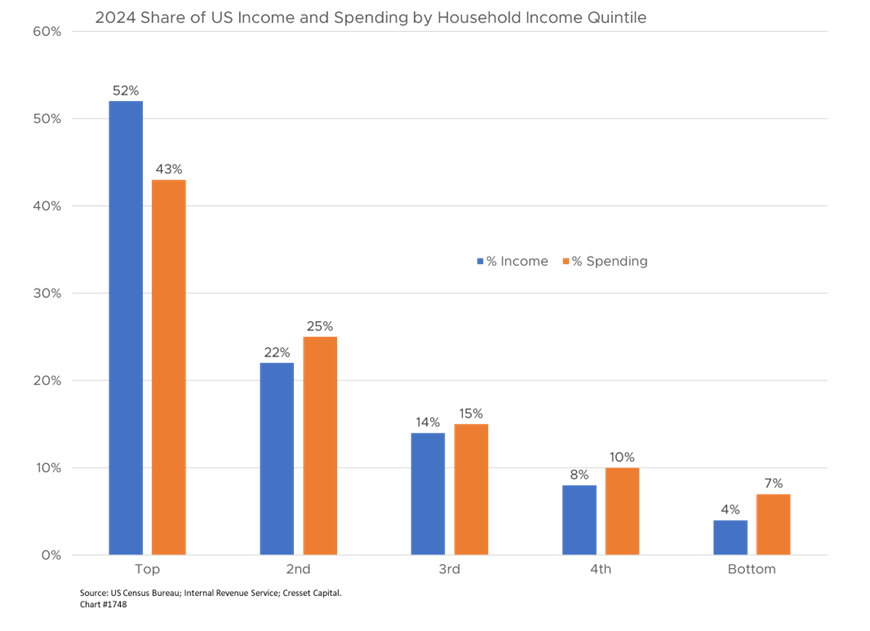

Job losses among high-income workers, particularly in sectors like technology, finance, professional services, and upper corporate management, can have a disproportionate impact on consumer spending and overall economic growth. Unlike lower-income households, which allocate most of their income to necessities, higher earners drive discretionary and luxury consumption. The top 20 per cent of high-income earners accounts for nearly half of all spending as well as a large share of spending on travel, dining, entertainment, home renovations, automobiles, and financial investments. When white-collar layoffs occur, these households tend to pull back rapidly on such spending, leading to ripple effects across industries that cater to affluent consumers.

Additionally, high-income workers often carry substantial fixed costs, mortgages, private education, and debt obligations that force sharper cutbacks elsewhere when income drops. The loss of confidence among these consumers can also weigh heavily on sentiment indices and broader market psychology, as they are more likely to own equities, real estate, and retirement assets whose values influence spending behavior through the “wealth effect.”

From a macroeconomic standpoint, a contraction in spending by top earners can have a multiplier effect. Businesses serving premium markets, from luxury retailers to travel companies, see immediate revenue declines, while middle-income sectors feel secondary impacts as demand softens throughout the supply chain. Because these households save and invest more, prolonged unemployment among them can also suppress capital formation and financial inflows. In sum, job losses among high-income workers not only curb immediate consumption but can erode confidence, weaken asset markets, and slow the cyclical engine of growth that depends heavily on their discretionary and investment spending.

Will Higher Productivity Lead to Higher Wages, or Just Corporate Cost Savings?

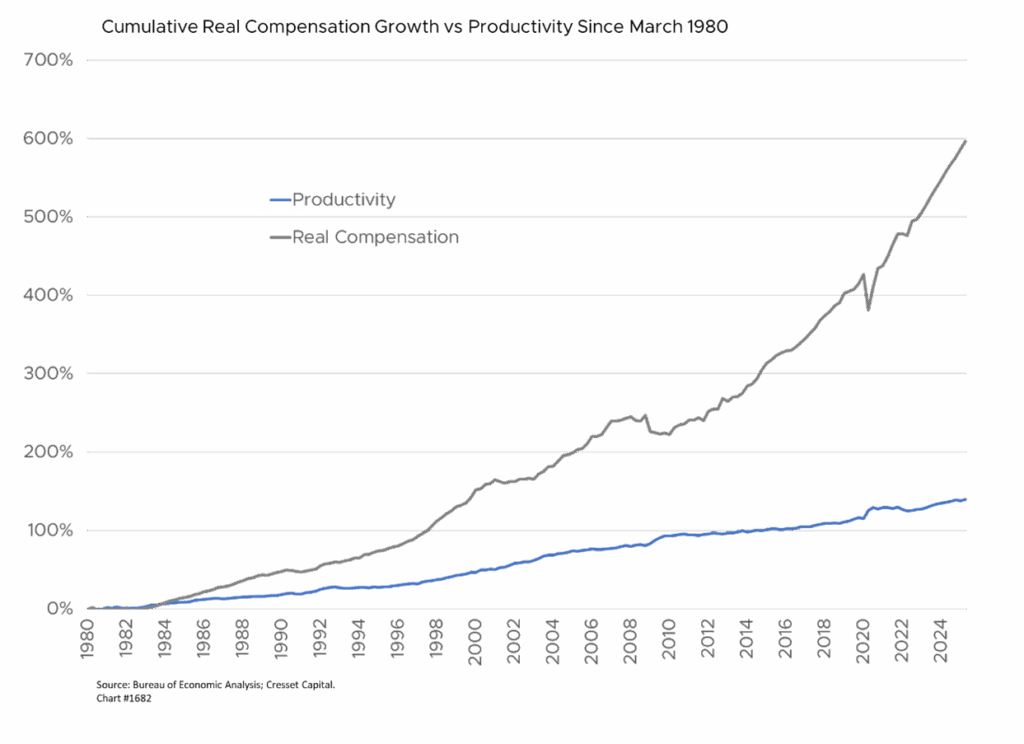

AI’s long-term economic effect depends on whether productivity gains translate into higher wages or simply corporate cost savings. Early evidence is mixed. AI investment contributed approximately 1.3 percentage points to US GDP growth in mid-2025, with business spending outpacing household consumption for the first time in years. Yet real wage growth for white-collar workers has stagnated.

If AI-driven productivity accrues primarily to shareholders and executives, income inequality could widen. Moreover, AI could amplify geographic divides, concentrating job creation in tech hubs while displacing roles in traditional business centers. However, we’re comforted that, historically, higher productivity has translated to real wage gains over the long term.

The current phase of AI integration resembles previous technological revolutions, with initial dislocation followed by long-term adaptation. As automation handles more routine tasks, human labor will increasingly shift toward judgment, creativity, and collaboration. In Sweden, 87 per cent of technology firms already use AI. Yet surveys show no net reduction in employment so far, although companies do anticipate staff cuts in their next adoption phase. This pattern – early experimentation followed by efficiency-driven consolidation – is likely to be repeated globally. The fact that job growth in the US has not kept pace with productivity since 2000 is a demographic limitation, not a technological one.

Bottom Line:

We expect AI’s impact on the job market to be profound, but not catastrophic. Large language models appear to be altering how we work more than whether we work. For now, layoffs attributed to AI often mask broader economic adjustments, tariff pressures, slowing growth, and corporate cost-cutting. But the long-term trajectory is unmistakable: routine and repetitive work, both manual and cognitive, will continue to decline, while demand for adaptive, creative, and technologically fluent workers will rise. We also note that while it’s relatively easy to identify specific jobs at risk, it’s much more difficult to envision new jobs that will be created by the technology.

The challenge for policymakers, educators, and employers is to ensure that this transformation expands opportunity rather than diminishes it. The future of work in the AI era will depend less on machines’ capabilities than on human choices, how we invest in skills, design organizations, and distribute the benefits of innovation. AI is excellent at “inside the bell curve” solutions. We still need humans to think outside the box.