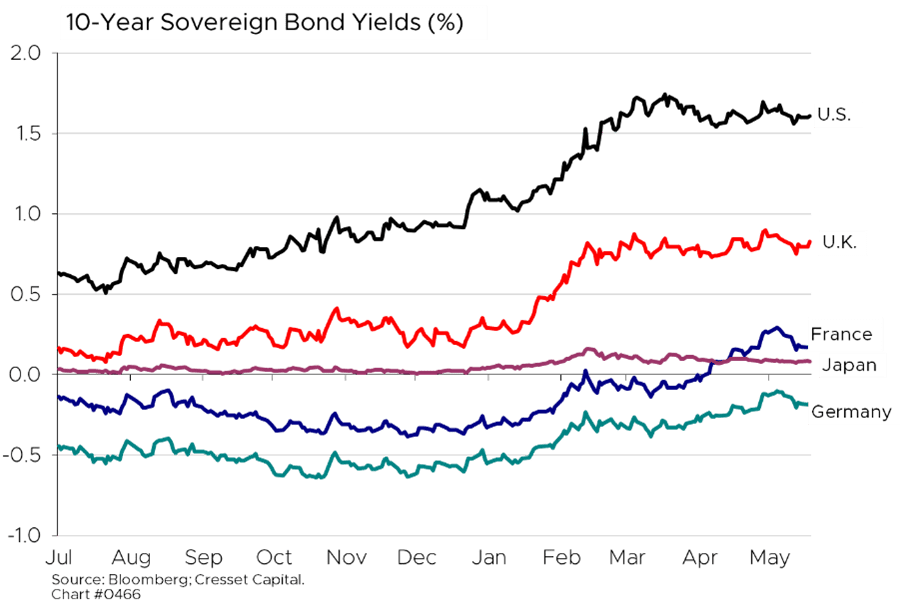

6/30/21: The pandemic took a toll on the global economy with its resultant lockdowns and travel restrictions, but it also aligned the global economy like never before. Even the global financial crisis, which centered in the US and Europe, left the Pacific Rim somewhat insulated. Now, thanks to vaccinations, the developed world is recovering en masse. Meanwhile, global central banks are aligned in their desire to not interfere with the global recovery, maintaining easy monetary policies as domestic growth and inflation rise. The synchronized decline and subsequent recovery have left global bond markets closely correlated and interdependent. As a result, bond yields have moved in lockstep this year, particularly between Europe, the UK and the US.

Jay Powell’s Federal Reserve laid the groundwork for how the developed world’s central banks are approaching synchronized reopening. The US central bank shifted its stance from monetary restraint, its decades-long preemptive approach of raising rates to ward off potential inflation, to one that pursues full employment – a policy, they believe, would benefit more Americans, particularly lower-income, unskilled workers. Under this new approach, any inflation flare-ups would be addressed after the fact. Meanwhile, consumer prices in the US are rising quickly, with 5 per cent year-over-year gains registered in May, representing the sharpest increase in 13 years. This “lower for longer” approach to interest rates has helped promote risk taking, not just in the stock and bond markets, but in corner offices as well. United Airlines, for example, recently announced a fleet overhaul with the biggest jetliner order in company history. The airline agreed to buy 200 Boeing 737 Max jets and 70 Airbus SE A321neo planes, a deal estimated to be worth $15 billion. Clearly, United leadership is betting on a global recovery.

The Bank of Japan (BoJ), cursed with a continually disappointing economy, pursued an inflation-overshoot strategy for the past five years with little to show for it. Japan’s inflation rate never threatened the bank’s 2 per cent target. With Japanese households and companies convinced inflation will stay near zero, expectations are deeply rooted, leaving the Bank of Japan helpless in pursuit of its inflation target. Japan’s economic recovery diverged from those in Europe and the US this year as the country struggles with its COVID-19 vaccination campaign and big cities, like Tokyo, continue to be partially locked down.

Japan’s monetary authority has backed away from aggressive stimulus in favor of a more “sustainable” policy. The bank recently scrapped its pledge to buy nearly $60 billion a year in equities, mostly through exchange-traded funds. Unlike the rest of the developed world, Japan’s property prices have not risen this year, likely leading to flat inflation readings in the coming months since housing costs are a major CPI component. The European Central Bank (ECB) shares the Fed’s view: it is willing to accept a higher level of inflation in exchange for improving economic and social welfare. Eurozone inflation pierced the ECB’s 2 per cent inflation target in May, but Lagarde & Company believe sustained inflation can not occur without ambitious fiscal spending. Like its global central bank brethren, the Bank of England (BoE) remains remarkably accommodative. Andrew Bailey asserts the UK’s current inflation bout, which is expected to exceed 3 per cent in the coming months, is “transitory” and should not affect their accommodative stance. The BoE has chosen to wait for inflation to subside before reassessing its monetary strategy, warning that the economy “will experience a temporary period of strong GDP growth and above-target CPI inflation, after which growth and inflation will fall back.”

Coordinated stimulus from the Fed, ECB, BoJ and BoE have kept rates below fair value and will continue to drive a low-rate, high-growth recovery. While the Federal Reserve plays an anchor role, US central bank policy only partially explains why US Treasury rates are as low as they are. Collective bond buying among the ECB, BoJ and the Fed hae over the years accumulated to nearly $24 trillion, with nearly $5 trillion of bond buying over the last 12 months.

US and soverign rates are historically low thanks to price-insensitive buyers who accumulate government debt issues by mandate. Foreign holders combined with the Federal Reserve hold half of all US Treasury bills, notes and bonds in circulation.

Eventually, the central bank bond-buying frenzy will abate; Fed watchers believe Chairman Powell could articulate his tapering strategy as early as August. In the meantime, with inflation on the rise and interest rates near zero, “real” rates – yields after inflation – have plunged. Negative real yields reduce purchasing power for bond holders and create a favorable environment for real assets, like commodities, including gold.